以《Triple Town》论述游戏基本情感及其诱发条件

作者:Danc.

激动人心的时刻到了。现在你可以体验网页版益智游戏《Triple Town》,我们已推出测试版本,会逐步进行优化。值得称赞的是,Cristian Soulos再次将作品变成大众关注焦点。

《Triple Town》是款特别的游戏。游戏在我设计的所有游戏中评价最高(94%)。这也是我多次重新设计的唯一一款作品。为什么会这样?

从表面看,游戏采用简单的消除模式,但体验一段时间后你就会发现游戏所蕴含的策略深度。其节奏非常罕见。游戏节奏缓和,玩家在游戏中随意做出系列小决定。这些小决定能够让高级玩家体验超过1个礼拜的时间。体验一段时间后,你发现自己玩的其实是《文明》的消除内容,你非常关心自己所建造的内容。这种强大情感反应总是令我倍感吃惊。

此次发行的内容最主要的添加内容?小熊。

小熊无处不在

《Triple Town》进一步巩固我创建游戏世界和背景的模式。我喜欢探索支撑游戏机制内在情感反应的途径。Kindle版本的设计相当抽象,融入许多象征符号和机制规则。游戏背景非常简单。但由于我自己玩过且还观察他人的体验情况,我发现游戏能够引起系列强烈情感:

* 自豪感:当你创造出美丽城市,你就会想要分享。大家会截屏,然后进行吹嘘。因所创建内容而感到自豪是驱动《Triple Town》玩家的主要情感。

* 好奇心:你想要知晓下个道具是什么样子。新手玩家常因此而努力获得城堡。

* 厌恶:你开始厌恶远程传送的忍者。它们没有攻击你,但会阻碍你的计划。

* 悲伤:首次杀死小熊时你会感到轻微的悲伤。然后你会开始学习如何抑制这种情绪。

* 生气:当命运在错误时间给你错误道具。

* 竞争:当你发现好友比你表现突出。

* 绝望:当你感到版面平台将要关闭,意识到自己无法赶上好友的时候。

* 安慰:当版块开始变填满,但你的一个神奇移动,令版图出现新的细长地带,让你能够重新进行操作。

游戏在激起这些基本情绪上表现突出。无需英雄之旅、故事以及包含沉浸性第一人称镜头的超现实画面。你可以通过机制设计基本原则创造情感丰富的有意义体验。

调整情感

当我重新审视《Triple Town》设计时,其中情感已非常清晰。但我希望探究自己如何更直接地让这些情感配合我的游戏构思。

情感是个复杂元素,所以我们需要找准切入点。大家普遍认为我们可以将情感分成大致几个类别。例如,“瞄准他人的消极情感”。在此粗略分类中,你会看到被我们称作显著情感的变体。例如,厌恶和生气其实高度关联,通常与由他人引起的失败或约束感有关。作为设计师,我要如何扩展引起常见情感的条件,获得我所期望的情感变体?

这有许多相关理论。在《Triple Town》中,我受到情感因素理论和体标记理论的影响。和人类认知许多方面一样,多种输入内容是最终创造优质体验的必要条件。红酒的“味道”是由实际化学味道和红酒的感知质量综合而来。标价100美元的5美元红酒会被认为比原瓶中的酒美味。同样,我们假设我们的大脑根据下述内容综合出最常见的基本情感:

* 模糊的身体反应(肾上腺素变活跃,心跳加速)。

* 所处情形的机制背景。

* 相关过去经验的回忆认知标签。

就《Triple Town》而言,身体反应和机制背景表现突出。我可以通过实验证明实我从玩家身上获得强大情感反应(游戏邦注:即便是通过非常抽象的游戏版面)。但认知标签尚未发展完善。所以此分析能够让我尝试一个特别的策略:

* 若你通过游戏机制激起常见情感反应,那么你可以将刺激因素运用至标签中,然后调节反应,获得特定情感。

怪兽或孩子?

参考《Triple Town》的一个基本标签范例。我所面对的原始信息是某观察发现:当他们杀死恼人NPC时感到极大宽慰。我尝试运用各种标记,获悉我们能够如何调节反应。

* 阶段 1:在建模初期,NPC意外呈现为小孩子。自然当玩家捕获这些孩子,将他们变成庄严石头时,他们会感到难过。意外死亡会带来愧疚和悲伤,而故意杀害则会让人觉得非常残忍。

* 阶段 2:所以后来我们将它们转变成邪恶的怪兽。这是个巨大转变。现在当玩家捕获和杀害怪兽时,他们会感到由衷的高兴。

* 阶段 3:最终在最新的架构中,我锁定眼神有些邪恶的小熊。很多人觉得杀死小熊没什么,但有些人会捉摸不定,感到不舒服。

* 未来:现在我开始深入情感空间,我已创建小熊角色,只要简单调整眼神,我就能够让小熊变得非常可爱,恢复愧疚和悲伤感觉。

从根本上来说,我是在平衡和调整玩家的情感反应。和席德·梅尔通过二元搜索锁定准确游戏背景类似,我通过试验各种极值,锁定适合情感。

运用能够获得情感共鸣的形象是个常见做法,但在实际操作中,NPC图标的作用与单放一个死去小孩的图像或截屏截然不同。小熊不是个单纯的形象。相反你需要创建独特的标签,其意义只体现在源自游戏体验的情感基础。丧失机制,你有的只是小熊图像。机制设定背景,提供大致情感反应,因此你能够创造优质情感体验。

避免不和谐情况

在首个阶段的小孩图像中,我看到了不协调因素。我们容易添加不适合的标签,混淆机制激发的情感。

《Triple Town》的核心是强烈自豪感和成就感。这些直接来自玩家创建6×6城市时惊人的长时间策略体验投入。设计巧妙的城市代表玩家几小时的精心劳作。

在Kindle版本中,我效仿《俄罗斯方块》和《宝石迷阵》的游戏理念。玩家体验游戏,获得积分,然后转向下个游戏。多数设计师都会借鉴被证实可行的原理,因为创新绝非易事。

遗憾的是,“明显”的设计选择与自豪感的逐渐创建相违背。这使得玩家只是点击按键,在创建新游戏的过程中,除去他们辛苦获得的成果。出乎意料的是,我多次将游戏放置在屏幕后方,不愿令它消失。“这不过是你完成的某个游戏回合,不妨继续前进”的理念不适合其他机制所创造的情感反应。

* 第一阶段:修复此问题的首个尝试包含添加硬币,这样就存在供玩家带到各城市创建回合中的持久资源。这作用显著,但显然还有不足。硬币只是个资源,玩家不会因失去某些简单的象征货币而感到悲伤。

* 第二阶段:第二个尝试就是玩家能够返回,在继续前进前浏览所创建的城市数次。这个方式作用显著,因为这让玩家获得告别机会。情感不协调情况体现在玩家能够以自己的节奏做出让步。这依然有所欠缺。

幸运的是,《Triple Town》是个服务,而不是发行后就被遗忘的游戏。

我后来设计游戏功能时,积极扩大其中自豪感。令我记忆犹新的经验是即便是像如何结束游戏这样简单的内容都涉及标记背景。若不是结束游戏,而是结束城市创建活动呢?

根据游戏机制导出游戏世界的寓意

这些单独情感体验创造了《Triple Town》的独特情感架构。由于存在不和谐,你无法简单将任何主题运用至此组动态情感,然后获得情感连贯的作品。相反,我们需要高度契合游戏机制的主题(游戏邦注:确保游戏机制激起的情感节奏与你所应用的标记存在明确联系)。

在《Triple Town》及我的多数设计中,游戏世界的主题和寓意都来自观看他人体验。我会观察和注意其中情感,然后询问关于所进行体验根本性质的问题。这是否是有关探索的游戏?创造?建造?若这是有关建造的游戏,符合当前独特架构的相关主题是什么?你是否在创建房屋?坟墓?此时NPC在做什么?

体验《Triple Town》几百小时后,我知道适合所有机制的寓意。《Triple Town》是有关殖民地主题的游戏。下面是些创建机制,以及源自寓意的标签如何以连贯方式将他们联系起来。

* 海外君王要求你在未被开垦过的土地上创建新城。

* 在这个过程中,本土居民不断在你的地盘上露面。他们不会攻击你,但会阻止你开垦。

* 所以你将他们赶到旁边。更有经验的玩家会创建小块保留地,将本土居民紧紧约束在里面。

* 由于过度拥挤,本土居民相继死去。

* 你用他们的骨头创建教会和教堂。

* 当出现顽固本土居民试图脱离保留地时,你可以派出自己的强大军队,移除祸害,然后继续自己的天召使命。

殖民主题和游戏机制的情感相当契合,我进行稍微调整,让其看起来没有这么天衣无缝。我没有选择特定受殖民统治的团体,而是将NPC变成道德模糊的小熊。向玩家呈现鲜明选择绝非难事(游戏邦注:这样玩家又回到原先模式中)。我对边缘情况更感兴趣,在这种情况中玩家进行自己认为合适的操作,然后随着时间的流逝,他们开始明白其行为带来的更大后果。在此游戏世界开发阶段,玩家应全心挖掘游戏机制,顾及游戏机制,确定自己的殖民者角色。

起初抽象的游戏定会逐渐变成丰富的游戏世界。城墙那边是什么?长久的殖民和帝国主义主题及其给当地居民文化带来的影响将在系列所设计中的游戏扩充内容中呈现出来。通过在标签上稍做变化,我得以调节系统有关殖民化主题的强烈情感。

同传统主题的差异

我发现这刚好相反,基于机制的主题风格和传统故事叙述大不相同。在注重叙述的游戏中,我总是先考虑角色、情节和信息,然后试图将支撑机制融入组合中。通常你会先向发行商定位游戏世界和角色,然后期望他们找到适合的玩法。思考下述两个典型叙述优先风格的寓意:

* 独特迷你游戏和谜题经常支持故事叙述:一个典型例子就是经典探险游戏,其中你利用的不是核心机制,而是系列符合情节的谜题。谜题的情感元素(游戏邦注:如沮丧和兴奋)同情节的情感节奏只有较少关联。通常为避免同各种故事情感节奏的不协调问题,谜题风格会进行定期转换。我们很难平衡一款游戏,但要求团队平衡系列较单薄的游戏只会导致出现浅层游戏机制。这出现在我细分玩法适应故事的过程中。

* 支持故事叙述的普通玩法:《最终幻想》之类的日本RPG游戏反复利用回合战略战斗机制呈现故事节奏。基于时间的策略战斗机制通常会创造基础情感,如失败、胜利、安慰,感到精力充沛及无力。无论所陈述的故事是什么,机制是用来提供情感支持。这样的模式在多数时候能够避免不和谐情况,但当情节转向非战斗领域,不和谐情况又会重新出现。这出现在所陈述的故事超越玩法支撑范围的情况下。

下面是些我遇到的设计误区。在某项目中,我创造某基于寻找根植于地中海的后Singularity文明遗迹的游戏世界(游戏邦注:大约是100AD)。在另一个项目中,我过度着迷于系列较小缠头生物。在两个项目中,我害怕改变世界。相反,我拼命创造新的游戏机制,希望能够找到适合游戏世界的内容。我几乎一无所获。就我看来,创造富有沉浸性的新游戏机制非常困难,成功机率也难以把握。但创造一个有效游戏世界的投入则相对较少。任何人都能够复制一个有效运作的游戏,顺利发行盗版作品,将其称作优秀作品。

现在我找到一个更好反映这些代价的哲学。玩法优先,空间创建源自玩法机制。更新玩法其实就是打破同特定空间的情感联系,放弃原有游戏世界,制作的新内容应不会让人感到不妥。设计师应该要创建支撑游戏的空间。

总结

《Triple Town》的主题和空间创建内容不是很多。习惯奢华作品(游戏邦注:这些游戏融入过多故事叙述内容)的玩家不会发现我所选择的标签(它们给游戏体验带来一定影响)。但他们及多数玩家都会清楚感觉到游戏节奏。

我在这里陈述的内容并不新颖。我所强调的是要自下而上地创建游戏标签和空间。先从机制着手,然后再寻找适合情感节奏的的标签。基于此玩法基础,你就能够创建游戏空间。

备忘录:调节基础情感的步骤

1. 创造有趣机制

2. 观察玩家在机制中的情感反应。

3. 调节机制情感诱发条件进而增加或减少某原始情感反应。

4. 只要掌握系列预期情感反应,你就可以讨论定义情感的自然标签。

5. 测试标签,查看其如何引起特定情感变体。

6. 将标签捆绑至游戏寓意(游戏邦注:游戏寓意主要传递和加强其独特情感架构)。

注解:情感的OCC模式

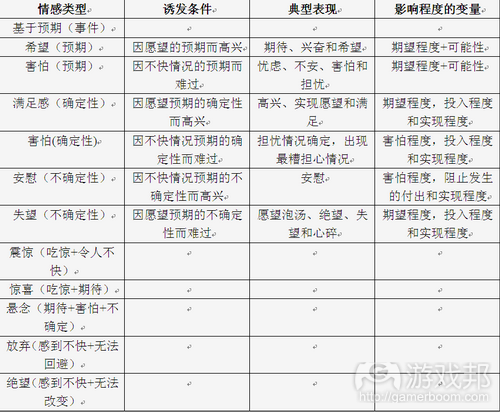

Aki Järvinen的论文《Games without Frontiers》谈到一个有趣情感模式(由Ortony、Clore和Collins提出,简称OCC模式)。模式假设情感结果同机制变体相关。例如,玩家沮丧感同可变“可能性”有关:

* 低可能性:若玩家预测特定结果,但根据过去经验,他们觉得几乎没有可能,他们通常不会过度失望。

* 高度可能:可能性很高,结果没有如此,沮丧感会更加突出。

通过调节可能性、投入程度或结果重要性等变量,设计师能够设定系列“诱发条件”。我喜欢这个术语,因为我们因此就具有讨论情感的合适词语,无需受人文科学的不必要干扰。通过合理设置游戏机制变体,你就能够创造生成特定情感的诱发条件。

将这些理念应用至游戏开发是个复杂过程,但仅作为理念框架,其力量就非常强大。下面是Aki制作的几个有效OCC图表,主要罗列条件、变量、主要情感类别和情感变体。

备注:视频游戏的超现实主义

通常优秀视频游戏都和现实世界脱节,也就是所谓的超现实世界。《马里奥》、《吃豆子》、《 Katamari》、《宝石迷阵》以及《Portal》这类的游戏都设定在超现实的空间中,其遵守协会逻辑原则,但可以违背现实世界的理念。更有趣的是尽管大量付出让我们的符号机制只是在表面上具有连贯性,但很多玩家都开心地沉浸于超现实世界中,对此毫无怨言。拖有什么不满,那就是设计师进行不必要的调整,结果带来许多不必要的不协调因素,要求玩家关注无关紧要的细节内容。

我觉得这个超现实现象是基于机制情感节奏创建游戏空间所带来直接结果。不断调整各种游戏标签,力图呈现游戏最佳部分,分化传统叙述过程。那么为何有个移动的海龟?因为他符合游戏机制。这是必要调整,超过限度只会加重游戏体验和开发的负担。最后,适当超现实标签是个有效元素,因为它能够给你带来大量空间,避免出现不和谐因素。由于和现有情感机制高度契合,他们通常会创造更强大的游戏体验。(本文为游戏邦/gamerboom.com编译,拒绝任何不保留版权的转载,如需转载请联系:游戏邦)

Triple Town Beta (Now with Bears)

By Danc.

Exciting times. You can now play our puzzle game Triple Town in your web browser. We are releasing it as a beta and the game should evolve quite substantially over time. Huge kudos to Cristian Soulos for making this project blossom after a long winter. You can play it here.

Triple Town is a special game. It has the highest user rating of any of the games I’ve designed (94%). It is also the only one of my designs that I go back to again and again. Why is this?

On the surface, it is a simple match-3 variant, but after a few games you’ll start noticing the strategic depth. The pacing is…uncommon. There’s a relaxed mellow rhythm to the game where you casually make dozens of micro decisions. Yet these decisions add up to games that can last upwards of a week for advanced players. After a while you realize you are playing the Civilization of Match-3 games and that you care deeply about what you are building. That burst of strong emotion always surprises me.

The big addition for this release? Bears.

Bears, bears everywhere

Triple Town helped solidify how I construct the world and setting in my games. My inclination is to look for ways of supporting the emotions inherent in the game dynamics. If you’ve ever played the Kindle version, the design is a rather abstract puzzle game with highly symbolic tokens and mechanical rules. It has only the briefest of settings. Yet as I played the game and watched other play, I realized that it evoked an intense spectrum of emotions. Here were some of the ones that I noticed:

* Pride: When you create a great city, you want to share it. People take screenshots. They brag. Pride in what they’ve built is the primary emotion that drives players of Triple Town.

* Curiosity: You want to know what the next item looks like. Some people are driven to get a castle for the first time.

* Hate: You learn to hate the teleporting Ninjas. They never attack you, but they end up blocking your plans.

* Sadness: You have slight sadness the first time you kill a bear. Then you learn to steel yourself against the emotion.

* Irritation: When fate gives you the wrong piece at the wrong time.

* Competition: When you notice that your friends are doing better than you.

* Despair: When you feel the board closing in and realize that you can’t possible catch up to your friends.

* Relief: When the board is filling up and then you perform a miraculous move that empties a swath of the board and helps you start afresh.

Games are great at eliciting primary emotions. They don’t need the Hero’s Journey, they don’t need story, they don’t need hyper realistic visuals with immersive first person cameras. You can create an emotional, deeply meaningful experience simply by using the fundamentals of system design.

(You can read a bit more on the theory of how games are unique suited to creating emotional experiences in my previous essay on Shadow Emotions and Primary Emotions. I include a small section at the end of this essay on the OCC emotion model that fits nicely with my process. Thanks, Aki!)

Tuning emotions

When I revisited the Triple Town design, the emotions were already clearly evident. However, I wanted to explore how I could more directly shape those emotions to fit my vision of the game.

Emotions are complex to say the least so we need some sort of entry into the topic. There’s a general consensus that you can divide emotions into rough categories. For example ‘negative feelings toward others.’ Then within those rough categories, you see variations that we recognize as distinct emotions. For example, hate and irritation are actually highly related and are typically related to a sense of loss or constraint caused by others. As a designer, how do I push the conditions that elicit a general class of emotion so that I can dial in the emotional variant that I desire?

There are a variety of theories. In Triple Town, I was influenced by the two factor theory of emotion and the somatic marker theory. Like many aspects of human cognition, multiple inputs are necessary to create the final refined experience. The ‘taste’ of wine is synthesized out of the actual chemical taste and the perceived quality of the wine. A five dollar wine labeled as a 100 dollar wine can be perceived to taste better than that same wine in it’s original bottle. Similarly, we posit that our brain synthesizes most common primary emotions out of the following:

* An ambiguous physical response (your adrenaline jumping and your heart rate elevating)

* The system-derived context of the situation you are in.

* Recalled cognitive labels of related past experiences.

Looking at Triple Town, both the physical response and the system-derived context are very much present. I can experimentally validate that I’m getting strong emotions from the players even using a highly abstract game board. However the cognitive labels are underdeveloped. So this analysis led me to try a particular tactic:

* If you can evoke a general class of emotions with game mechanics, then you can apply evocative stimuli to label and therefore tune that response to elicit a specific emotion.

Monsters or children?

Consider a very basic example of labeling in Triple Town. The raw materials I was working with was an observation that players felt immense sense of relief when they killed annoying NPCs. I experimented with applying various labels to see how we could tune the response.

* Pass 1: During one early prototype, the NPCs were accidentally displayed as small children. Naturally, players felt bad when trapped them and they turned into grave stones. Accidental deaths led to guilt and sadness while deliberate deaths evoked a dissonant feeling of cruelty.

* Pass 2: So next we switched them to evil looking monsters. This was a dramatic change. Now players felt righteous glee when they trapped and killed the monsters.

* Pass 3: Finally, during this latest build, I settle on bears that have slightly evil looking eyes. Most players feel fine killing the bears, but for some there is a slight edge of ambiguity that makes them uncomfortable.

* Future passes: Now that I’ve explored the emotional space a little, I’ve set up the bears so that with one simple tweak of the eyes, I can make the bears incredibly cute and bring back many of the feelings of guilt and sadness.

In essence, I was balancing and tuning the player’s emotional response. Much like Sid Meier using a binary search (“double it or or cut it by half”) to narrow in on the correct setting in his game, I was trying out various extremes to narrow in on the appropriate emotion.

Using evocative imagery is a common enough practice, but in practice the labeling of NPCs is functionally quite different than merely putting up a picture or cut scene of a dead child. The bear is not an image for the sake of being an image. Instead you create a distinct label that is only meaningful due to how it builds upon an emotional foundation derived from play. Without the mechanics, you just have a picture of a bear. With the mechanics setting the context and providing the raw emotional reactions, you craft a carefully refined emotional moment.

Avoiding dissonance

With the children images in the first pass, I saw an example of dissonance. It is easy to add a poorly fitted label that confuses the emotions the mechanics are eliciting.

The heart of Triple Town are the strong feelings of pride and accomplishment. These comes directly from the rather amazing investment in extended tactical play that the player exerts when creating their 6×6 city. A well crafted city can represent hours of carefully considered labor.

In the Kindle version of the game, I used the sort of end game tropes that you find in Tetris or Bejeweled. You play the game, you get a score and then move onto the next game. Most designers rely on proven fallbacks to get the job done since it is difficult to always be reinventing the wheel.

Unfortunately, this ‘obvious’ design choice conflicted rather painfully with the slow and steady building of pride. There comes a point at which the player presses a button and in the act of creating a new game, erases all their hard earned progress. It is surprisingly how many times I’ve let the game sit on the last screen, not willing to leave it behind. The label of ‘its just a game session that you finish and move on from’ didn’t fit the emotional response that the other systems were creating.

* 1st pass: The first attempt at fixing this involved added coins so there is some persistent resource you take with you after each city. That helps a little, but not enough. Coins are merely a resource and players weren’t sad because they were losing some simple generic token.

* 2nd pass: The second attempt involved the ability to flip back and look at your city a last few times before you move on. This was quite effective since it lets the player say goodbye. The emotional dissonance was channeled into an activity that let players come to terms with it at their own pace. This still isn’t good enough.

Luckily Triple Town is a service, not a game that gets launched and forgotten. As I design future features, I’m explicitly creating them to amplify the feeling of pride. Fresh in my mind is the lesson that even something as simple as how to end the game involves labeling the context. What if instead of ending the game, you are finishing cities?

Deriving the world’s metaphor from gameplay

These individual emotional moments form a unique emotional fingerprint for Triple Town. Due to dissonance, you can’t simple apply any theme to this set of dynamic emotions and still end up with an emotionally coherent game. Instead, you want a theme that fits the mechanics like a glove where the emotional beats elicited by the system dynamics have a clear connection with the labels you’d applied.

With Triple Town, as with most of my designs, the theme and metaphor for the world came from watching people play. I would observe and note the emotions and then ask questions about the fundamental nature of the experience that was evolving. Is this a game about exploration? Creation? Building? If it is a game about building, what is a related theme that matches the current unique fingerprint? Are you building real estate? A tomb? What are those NPCs doing if that is the case?

After playing many hundreds of hours of Triple Town, I settled upon a metaphor that fit all the nuances of the mechanics. Triple Town is a game about colonization. Consider the following common dynamics and how labels derived from the metaphor tie them together in a coherent setting.

* You’ve been ordered by the empire from across the sea to build a new city on virgin territory.

* In the process, natives (depicted as less than human) keep showing up on ‘your’ land. They never attack you, but they keep preventing you from expanding.

* So you push them off to the side. More experienced players create small reservations and pack the natives in as tightly as possible.

* Due to overcrowding the natives die off en mass.

* You use their bones to build churches and cathedrals.

* When particularly difficult natives appear that seek to escape your reservations, you bring out your overwhelming the military might and remove the pest so you can continue with your manifest destiny.

The match between the theme of colonization and emotions of the mechanics was so strong, I tuned it back slightly so it wasn’t quite so on the nose. Instead of selecting a recognizable group that suffered under colonization, I made the NPCs into morally ambiguous bears. It would have been very easy to present players with a choices that were obviously black and white where players fall back on pre-learned schema. However, I’m more interested in the edge cases in which a player does something they feel is appropriate and then as time goes on they begin to understand the larger consequences of their actions. At this point in the development of the world, player should naively explore the system and due to the dynamics of game, then form a strong justification of their role as colonists.

What started as an abstract game is slowly but surely turning into a rich world. What is beyond the city walls? Long term, the themes of colonization, imperialism and the impact on native cultures will unfold over a series of planned game expansions. With slight variations in labeling, I should be able to tune in a variety of powerful emotions related to the theme of colonization.

Differences from traditional theme generation

I find this bottom ups, mechanics-centric method of theme generation quite different from a traditional process of storytelling. In a narrative heavy game, I think about characters, plot, or message first and foremost and then attempting to fit supporting gameplay into the mix. Often you pitch the world and characters to a publisher and then are expected to come up with gameplay that fits. Consider the implications of these two popular styles of narrative-first development:

* Unique mini-games and puzzles used to support narrative: One extreme example of this is your typical adventure game where instead of a core mechanic, you have a series of plot appropriate puzzles. The emotional aspects of the puzzle (frustration, delight) are only marginally related to the emotional beats of the plot. Also, in order to avoid dissonance with the wide variety of emotional beats that the story requires, the style of the puzzles is switched up on a regular basis. It is hard enough balancing one game, but asking the team to balance dozens of tinier games results in shallow systems throughout. I think of this as chopping up gameplay to fit the

* Generic gameplay that supports the narrative: A Japanese RPG like Final Fantasy repeatedly uses turn-based tactical combat to illustrate story beats. The time-tested tactical combat system usually produce a handful of primary emotions such as loss, victory, relief, feeling powerful and feeling powerless. No matter what story is being told, the same system is called upon to provide emotional support. Such a pattern avoids dissonance the majority of the time, but then when the plot veers into non-combat area, the dissonance comes back full force. I think of this as telling more story than the gameplay can naturally support.

Some of the most painful design rat-holes I’ve have ever dug myself into followed these patterns. In one project, I created a world based off finding relics from a post-Singularity civilization (circa 100AD) deep in the Mediterranean. In another, I was overly attached to a set of small bobble-headed creatures. For both, I was afraid to change the world. Instead, I desperately iterated upon new game mechanics, hoping to find one that fit my world better. And I rarely found one. As far as I can tell, creating a compelling new game mechanic is hard and success is unpredictable. Yet creating a functional game world’s is surprisingly cheap. Any idiot can copy a working game, toss some pirates on top and call it good.

Now I follow a different philosophy that better reflects these costs. Gameplay comes first and the worldbuilding are flow from the dynamics of play. If, as you iterate upon gameplay you make a rule change that breaks the emotional connection with a particular world, you should feel very comfortable tossing that world aside and starting fresh. Create a world that supports the game, not the other way around.

Conclusion

The amount of theming and world building in Triple Town is still quite light. Those of players used to the extravagant productions that burden a game with an overworked story may not even recognize the labels I’ve choosen as having an impact on your experience. Yet they do and most players will feel the emotional beats of the game quite clearly.

Nothing I’ve outlined here is new. The important insight for me has been creating the labels and world for a game as a bottoms up process. You start with the mechanics and then find the labels that fit the emotional beats. From this game play foundation, you build the world.

Cheat sheet: Steps for tuning primary emotions

Here’s the process for tuning emotions

1. Create a playful system.

2. Observe the emotional reactions of the player within that system.

3. Adjust the system’s emotion eliciting conditions to increase or decrease particular raw emotional reactions.

4. Once you have a rich set of desired emotional responses, brainstorm natural labels that refine the emotions.

5. Test the labels and see how they elicit specific emotional variations.

6. Bundle the labels into a metaphor for your game that communicates and amplifies its unique emotional fingerprint.

Note: OCC Model of emotions

Aki Järvinen’s thesis “Games without Frontiers” (pdf) pointed me towards a fascinating model of emotion by Ortony, Clore and Collins (OCC). It posits that emotional outcomes are tied to systemic variables. For example the strength of a player’s dissapointment would be tied to the variable ‘likelihood’

* Low likelihood: If the player predicts a particular result, but they know from past experience that it is highly unlikely, they typically won’t be overly dissapointed.

* High likelihood: Yet the likelihood is high and the outcome doesn’t occur, dissapointment will also generally be more pronounced.

By adjusting variables such as likilihood, degree of effort or value of results, the designer crafts a set of ‘eliciting conditions’. I love this phrase since it gives us game friendly terminology for discussing emotion without reverting to the fuzzy non-functional handwaving of the humanities. By setting your system variables appropriately, you can create eliciting conditions that spark specific categories of emotion.

There is far more work to be done applying these ideas to game development, but as it stands the conceptual framework is already really quite powerful. I’ve referenced here several useful OCC Charts that Aki assembled that list conditions, variables, main emotional categories and emotional variants. (I do recommend you read the full thesis. It gives a bit more context and it also one of the more clearly written works and easily consumable works to come out in recent years.)

Note: Surrealism in video games

Often the best video games have disjointed, narratively surreal worlds. Mario, Pacman, Katamari, Bejeweled and even a game like Portal take place in distinctly surreal locations that obey the logic of association, but are freed from the logic of the real world. Even more interesting is that despite immense amounts of effort making our labeling systems externally consistent (They aren’t ‘save points’, they are regen tanks), the vast majority of players happily engage in surrealist worlds with nary a complaint. If anything, the unnecessary justification introduces more unnecessary dissonance into the game by asking the player to pay attention to details that don’t functionally matter.

I see this surrealist aesthetic as the practical outcome of deriving the world from the emotional beats of the gameplay. The constantly tuning and tweaking of various labels needed to bring out the best parts of your game fragments the traditional narrative process. Why is there a walking turtle? Because it fits the mechanics like a glove. That is all the justification that is required and layering on more burdens both the experience and the development process. In the end, light surrealist labels are a positive thing since they gives you substantial wiggle room to avoid dissonance. And due to the solid fit with existing emotional dynamics, they often yields stronger game-centric experiences.(Source:lostgarden)